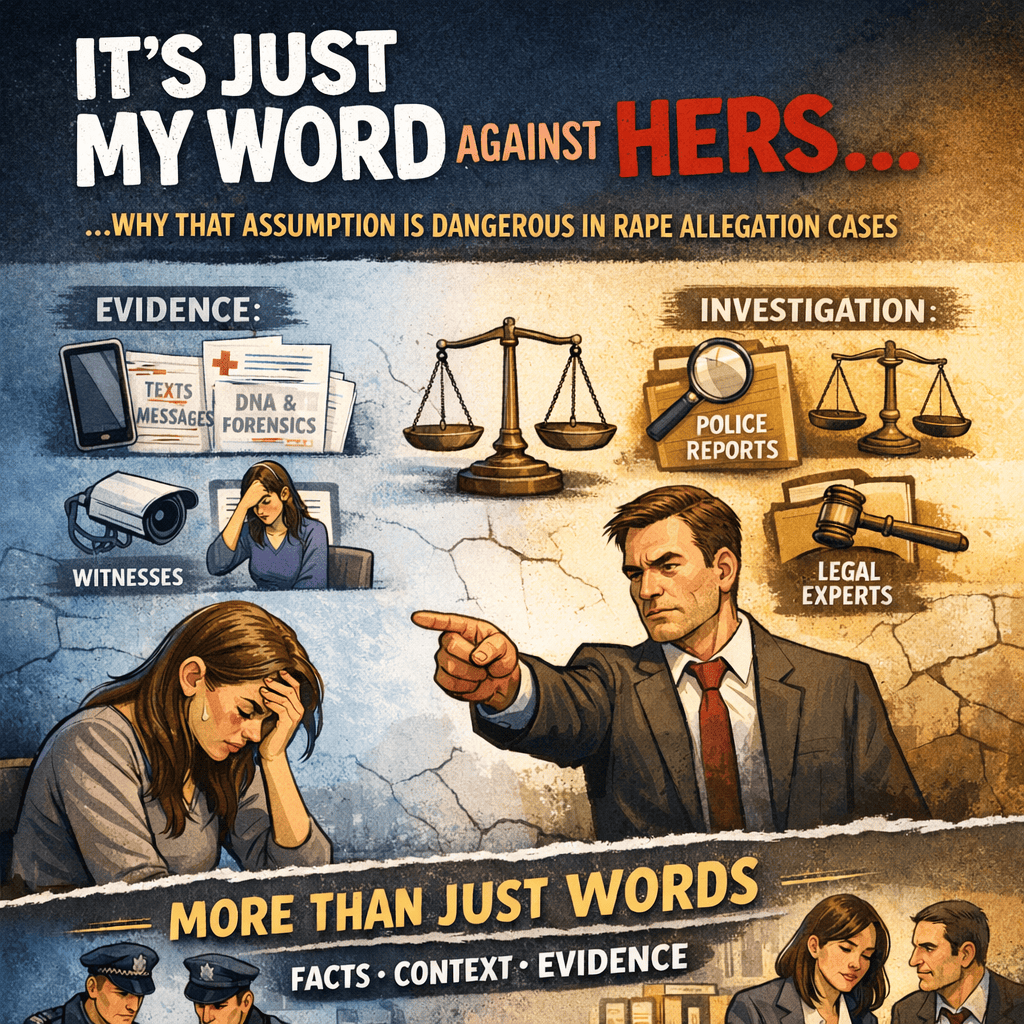

One of the most common—and most dangerous—assumptions I hear from people accused of rape is this:

“I’ve denied it. There are no witnesses. It’ll be my word against hers and that won’t be enough to charge me.”

Clients are often shocked when I tell them, sometimes very early on, that I think they may well be charged. They’ve read online statistics showing low charging rates, or been told by friends that rape cases rarely go anywhere, and they understandably assume that a denial equals safety.

That assumption is wrong.

This blog explains why rape allegations do not fail simply because they are denied, why headline statistics are a poor way to assess risk, and how the CPS actually approaches charging decisions in modern cases.

High attrition does not mean low risk

It is true that rape cases have a high attrition rate overall. Many reported allegations never result in a charge.

But this is where people go wrong: high attrition does not mean cases collapse because they are “one person’s word against another’s.”

At the pre‑charge stage, cases fall away for a range of reasons, most commonly:

- complainant disengagement (by far the most frequent reason);

- investigative delay, particularly around digital material;

- difficulty identifying a suspect; and

- evidential issues that are specific to the individual case.

In practice, well over 90% of rape cases that do not result in a charge do so because the complainant disengages and/or the suspect is not identified. Not because the allegation is neutralised by a denial.

Interpreting criminal justice statistics in this area is complex and often misunderstood. Quoting headline figures without context creates a false sense of optimism and can lead people accused of rape to underestimate the seriousness of their position.

Denial does not create a “score draw”

This is the point clients find hardest to accept.

Rape cases do not fail by default because the suspect denies the allegation.

There is no legal requirement for independent witnesses. There is no requirement for forensic evidence. There is no requirement for corroboration.

Rape cases are routinely prosecuted on the basis of the complainant’s evidence alone, provided that the CPS considers that evidence to be credible and capable of meeting the charging test.

A denial is expected. It is not a trump card.

How the CPS and juries approach the evidence

Another common misconception is that if two people give opposing accounts, the case is treated as evenly balanced.

That is not how the law works.

Juries are not asked to count votes. They are directed to assess credibility and reliability. In practice, this means looking at factors such as:

- whether the complainant’s account is coherent and internally consistent;

- whether it fits with surrounding evidence such as messages, calls, location data, or third‑party accounts;

- whether there are reasonable explanations for the delay in reporting or apparent inconsistencies;

- what the complainant did before and after the alleged incident;

- and—critically—whether the defence account stands up when properly examined.

If a jury is sure that the complainant is telling the truth, that alone is sufficient to convict.

The fact that the accused gives a different account does not “cancel out” the prosecution's case.

The modern direction of travel

Anyone defending a rape allegation needs to understand the broader context.

Since the Me Too movement, and following significant policy changes within the police and Crown Prosecution Service, there has been a clear shift in emphasis:

- greater focus on progressing cases rather than allowing them to fall away early;

- increased willingness to charge cases based on complainant testimony where the evidential threshold is met;

- a move away from treating rape cases as inherently “too difficult” to prosecute.

This does not mean every allegation results in a charge. But it does mean that relying on outdated assumptions about how these cases are handled is risky.

Why statistics don’t decide your case

Clients often want reassurance. I understand that. But I don’t believe in telling people what they want to hear.

General statistics do not decide individual outcomes. The CPS does not charge by percentage. They charge fact by fact, applying the evidentiary test to the material before them.

The only meaningful way to assess risk is to examine:

- the complainant’s account in detail;

- the surrounding evidence;

- the weaknesses, inconsistencies, and opportunities for forensic challenge; and

- how the case is likely to be viewed if tested.

That is where cases are won or lost.

Straight‑talking defence in rape allegation cases

I tell clients the truth, even when it’s uncomfortable. People sometimes describe that as pessimism. I see it as realism.

I win cases by forensically deconstructing the complaint. The more information we have, the more detailed and effective the deconstruction can be. Denial alone is not a strategy.

If you are under investigation for rape or sexual assault and assuming that “it’s just my word against hers,” now is the time to get proper advice from a solicitor who understands how these cases actually work—not how people on the internet think they work.

The focus must be on the evidence in your case, not on comforting but misleading averages.